Nearly two years ago, ChatGPT’s AI writing powers set off a firestorm in classrooms. How would teachers be able to determine which assignments were actually authored by the student? A host of AI-powered services answered the call.

Today, there are even more services promising to catch AI cheaters. But teachers aren’t necessarily jumping on board. Instead, they’re returning to a more traditional solution: pen and paper. No phones, no laptops, no Chromebooks. Just a student and their (biological, not silicon) memory.

My own kids — one in a California middle school, the other in high school — aren’t happy about it. “My hand cramped up so much,” my eldest son complained about his AP World History course he took last year, and the requirement to handwrite all papers and tests because of AI concerns.

My younger son groaned aloud when I read him his middle-school science requirements for the 2024-25 school year: Write the assignment down on paper and then, if needed, type it up. But his teacher was clear. “While AI offers significant potential benefits, middle-school students may not have the maturity or background needed to use it effectively,” she wrote in a note to parents.

The AI detectors

So why bother with old-fashioned methods when, as noted, a number of AI detectors exist?

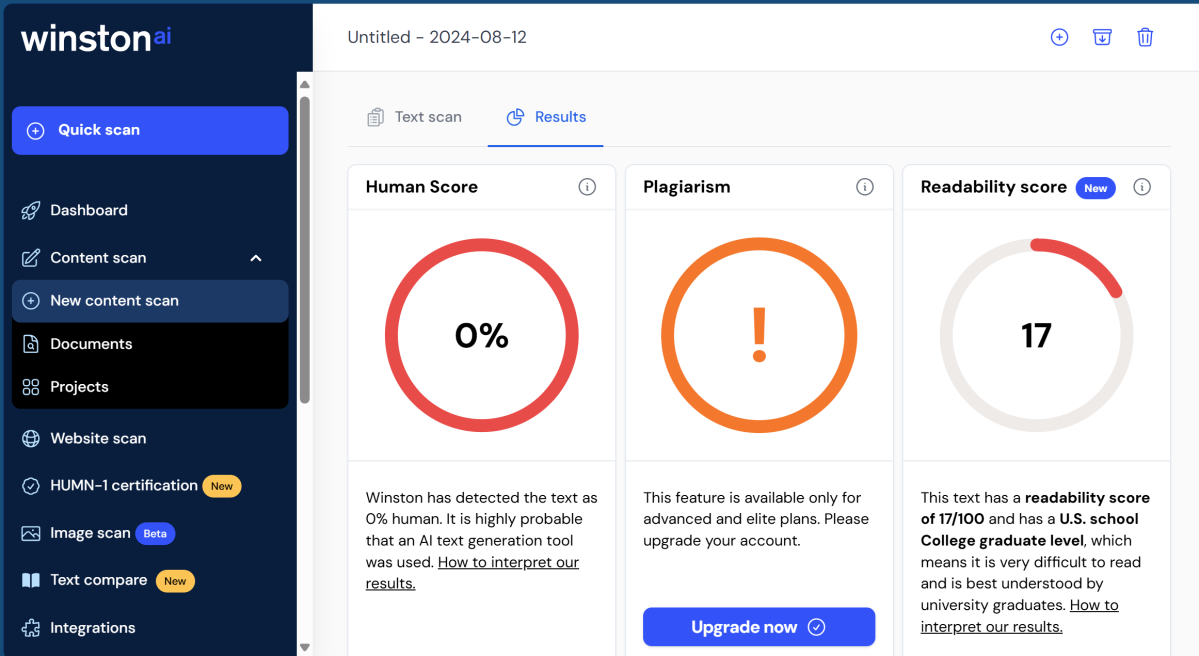

Contentatscale.ai, GPTzero.me, Winston.ai, and more, offer free or subscription-subsidized AI detection services. Upload the content, and they’ll tell you whether AI wrote the words. Paid sites, such as Turnitin, offer more sophisticated detection services for larger fees. The services are designed to step in and play the role of a traffic cop, flagging AI-generated essays but letting truly original content through.

If AI-powered tools to detect AI were foolproof, it all might work. But they’re not. To date, the teachers and professors I interviewed said they haven’t found a totally accurate way of detecting AI-generated content. The lack of certainty undermines the validity of any accusation a teacher might make. And with potentially thousands of dollars of tuition on the line, a charge of plagiarism is a big risk for everyone involved.

Pixabay via Pexels

AI checkers aren’t smart enough, teachers say

AI detection tools never got off to a good start. In 2023, OpenAI released its first AI checker, Classifier. Developed by OpenAI after its release of ChatGPT, Classifier identified 26 percent of AI-authored text as human, and said it could be fooled if AI-authored text was edited or modified. “Our Classifier is not fully reliable,” OpenAI said, point blank.

Classifier was retired seven months later “due to its low rate of accuracy,” OpenAI said.

Just a short time ago, OpenAI took another stab at detection, citing two methods — watermarking AI content and labeling it with metadata — as potential solutions. But watermarks can be avoided by simply rewriting the content, the company said. A tool to apply the second method, metadata, has yet to be released.

Such inaccuracy has made some schools gun shy about using AI detection. Bill Vacca, director of instructional technology at Mohonasen Central School District in New York said that he hasn’t found any qualified AI checkers. “And I’ve tried them all,” he said.

There are numerous problems, Vacca said. For one, the constant updates to ChatGPT and other AI tools means that AI checkers need to constantly respond. Some sites stay up, then unexpectedly vanish, he said. Furthermore, the sites’ results don’t always instill confidence. Instead of definitively stating that a piece of content is “100 percent AI,” the sites can offer a wishy-washy 50 percent or 25 percent recommendation. That’s not good enough.

According to Vacca, those scores aren’t good enough to justify using an AI checking site. “It’s too hard to determine. And that’s when we realized that it’s not as simple as we thought it would be.”

John Behrens, the director of the office of digital strategy at the College of Arts and Letters at the University of Notre Dame, agrees. “People have to be very clear about the statistical capabilities of those detectors, and I’ve seen some of those detectors that are worse than nothing,” he said. “I mean, statistically worse than not using anything.”

Another factor is that uploading a student’s content without permission can violate school, state, or even federal rules, such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, or FERPA.

San Jose State University in California doesn’t use AI detection tools, according to Carol-Lynn Perez, a senior lecturer in SJSU’s Communication Studies department that PCWorld spoke with. Perez cited a May email sent by Heather Lattimer, the dean of SJSU’s College of Education and the interim provost of undergraduate education, which stated that uploading a student’s work violates two university policies and possibly FERPA. Lattimer also noted the risk of false positives in her email.

The university provides its own AI detection tool within Canvas, SJSU’s learning management system, and lets students know that the faculty has access to it. But Canvas can be used “only as a jumping-off point to start a conversation with our students about AI usage, and not as definitive proof that they have used AI,” Perez said in an email.

Ardea Caviggiola Russo, the director of the office of academic standards at Notre Dame, said that the university looks for “red flags,” such as sources that don’t exist, content not covered in class, advanced terminology, and a general inability of the student to discuss their own work.

“Regarding AI detectors, we opted not to turn on Turnitin’s AI detector when it was made available last year, mostly because of the concern about false positives that you mentioned,” Russo said in an email. “And also, we just felt like we didn’t know enough about the AI detection tools generally to use them responsibly. Now, my office does subscribe to a detector that we use if a professor is suspicious of a student’s work for whatever reason, but even a 100 percent likelihood isn’t enough on its own for an accusation, in my opinion.”

In a statement, Turnitin agreed. “At Turnitin, our guidance is, and has always been, that there is no substitute for knowing a student, their writing style, and their educational background,” the company said in an emailed statement. “AI detection tools, like Turnitin’s AI writing detection feature, are resources, not deciders. Educators should always make final determinations based on all of the information available to them.”

Do AI checkers actually work?

To be fair, some of the AI detection services do seem to work.

I copied the text of an editorial I had written about Logitech’s concept of a “forever mouse,” removed the captions and subheadings, and dropped the text into several AI detection services, many of which are free for basic scans. They included Contentatscale.ai, GPTzero.me, Winston.ai, CopyLeaks’ AI Content Detector, Originality.AI, Writer.com’s AI Content Detector, Scribbr’s AI Content Detector, Sapling.ai’s AI Detector, ZeroGPT.com, and ContentDetector.AI. (Thanks to BestColleges.com’s list of AI detection tools.)

Of the 11 tools, all but one identified the content as human-authored, and by enormous margins — all gave a less than 10 percent chance that it was generated by AI. The exception: Originality.ai, which returned a 93 percent chance that the copy was AI-authored.

I then asked ChatGPT for a five-paragraph essay on the effects of the French Revolution on world politics. Every single service identified the content as clearly AI-generated, save for Writer.com, which said that ChatGPT’s essay had a 71 percent chance of being written by a human.

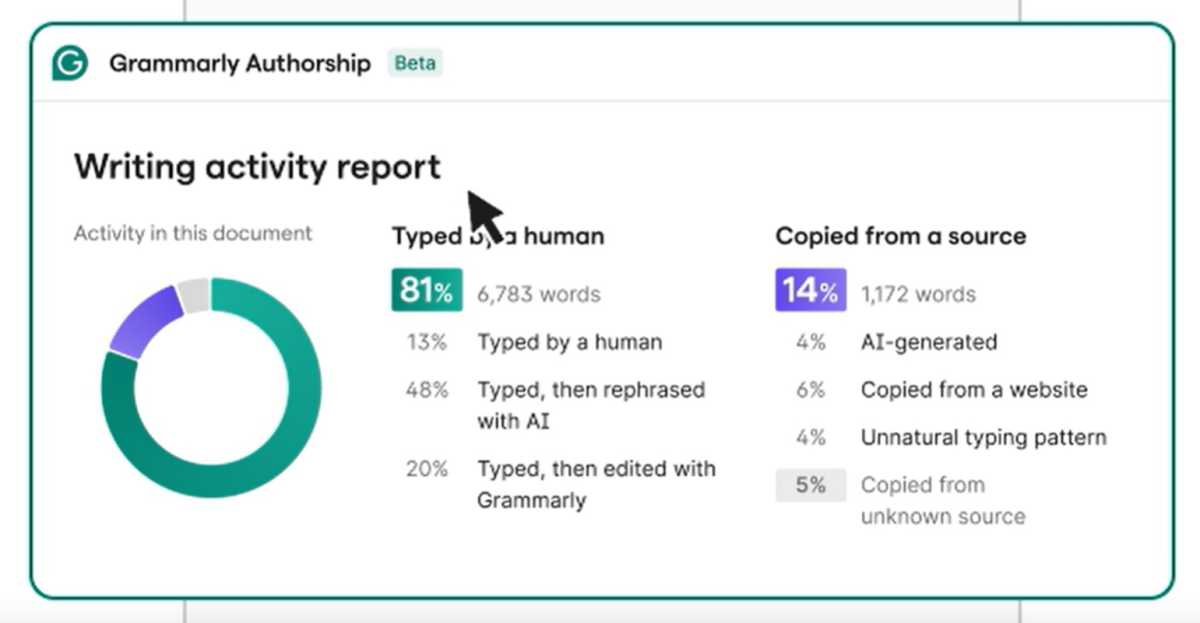

Some services are trying to split the difference. Grammarly’s new Authorship service, for example, tries to identify which words are original, which are AI-generated, and which are edited by AI — with the idea that students may combine elements of each.

Grammarly

A better way to detect AI: Work with the student

So how do you fight AI? Teachers say that the best way to tell if a student is cheating using AI is to understand the student, and their work. And when in doubt, ask them to prove it.

“The simple solution was take out a piece of paper, and ask them to show me how you are solving this,” Vacca said. “That killed [the issue of] a lot of the students cheating.

“They’ve tried things like dumbing down their answers, but it’s still easy enough to detect that it’s not their exact writing,” Vacca added.

Perez agreed.

“When there is concern about unethical usage of AI in the classroom, we should do due diligence in our investigation,” she said. “First, we need to familiarize ourselves with each individual student’s writing. Second, we should compare the material we feel is AI generated with their initial writing so we can see if the grammar, sentence structure, and writing style are consistent with the students writing. Third, we need to either chat with the student face to face or through email so we can get their version of what occurred.”

Pexels/ Yan Krukau

Perez said she read a student paper that an AI tool indicated had a 90 percent probability of being AI-generated content, and that sounded “very mechanical.” She emailed the student and asked for an explanation, and the student denied using AI. She then followed up via video.

“During the video call I asked the student to speak about the content of the paper, and they could not speak about the paper or the content of the course up until that point, which proved to me that the AI detection was correct,” Perez added. “I requested the student rewrite the paper in their own words, and they were reported to the university for further sanctions.”

Teachers that I spoke to said they don’t like being placed in an adversarial role, and would rather focus on what they do best: teaching.

Nathaniel Myers, an associate teaching professor at Notre Dame, said he’d rather create “a space where students feel comfortable being transparent, so that we can think through these things together.” SJSU’s Perez said a number of professors involved in Facebook groups tailored to AI in the classroom have reported mental health issues, and that it was demoralizing to see so much unethical AI use in the classroom, creating even less job satisfaction.

The pressure, though, falls on both teachers and their students, and both are also turning to AI to ease their burden.

“What you’re trying to do is pit AI versus AI,” Nitesh Chawla, a professor of computer science and engineering at Notre Dame, said. “One AI is creating content. The other AI is trying to detect if some other AI created that content. You’re pitting them against each other. I don’t even know what that means!”