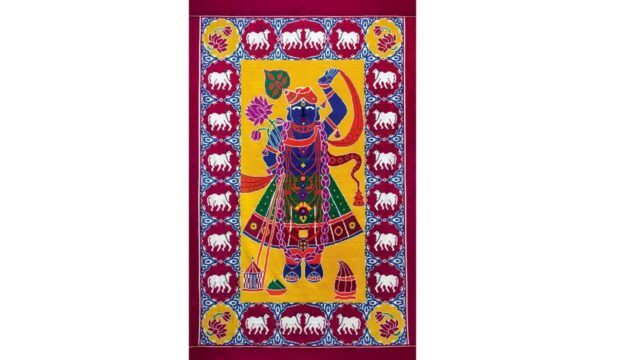

Shrinathji stands with a fully bloomed lotus next to his left arm, surrounded by plants. His calm and resolute gaze notices a lively chorus of cows. The simplicity of expressions transports you to the rustic dinner of the art of two medieval temples. However, it is not just the faces or the spiritual quality of Gaurang Shah's frescoes that captivates – and how he brings his luxurious, high-chrome gowns to life.

The softness and movement of imitation fabric does not interrupt Jamdani in Swarup, a 24-piece series of artisan textiles and fabrics. The geometric patterns of Srikakulam create a divine silhouette, while the monumental Venkatagiri tapestry adds serenity and the Balinese ornaments of Srinagar heighten the grandeur of Shrinathji.

This Shrinathji mural (58 x 47 inches), made from hand-embroidered raw silk fabric, takes 65 days to grow in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh

Each fitting, tying and varvalhar is done with hypnotic effect using chikan from Lucknow, hand tie dye and duplo ikat from Patan, gota patti from Jaipur and Ari embroidery from Kaksimira, Dehradun, Hyderabad and Dhaka. You paint traditional Indian painting styles, each with its own distinct history. Narration of Orissa through visual resources, Pattachitra, Kalamkari narrative TirupatiThe sumptuous paintings of Tanjore from Tamil Nadu and the folkloric scrolls of Cheriyal from Hyderabad have been meticulously recreated in the past.

Swaroop will premiere at the end of August in Hyderabad and 15 pieces will be on display at the Taj Palace in Mumbai on October 18 and 19 as part of the Shah exhibition featuring handwoven sarees and ghagra. “My first love is your sarees,” shares Shah. “The six meters of fabric provide a unique versatility for non-film creativity, especially with the intricate jamdani. You simply cannot reach the same depth of design in ghagra!”

Textile artist Gaurang Shah shares a moment with textiles at one of his jamdani units in Alikkam village, Srikakulam district, Andhra Pradesh

The Shrinathji collection is based on Shah's 2020 display case which contains 37 pieces Khadi Jamdani sarees, each one with hand-woven fabric that recreates paintings by renowned artist Raja Ravi Varma. These sarees are part of the Khadi: A Canvas project curated by Lavina Baldutta. “I need more challenges,” Shah said. “I want to be known for more than just what I wear, and explore different ways with texts.” Shah, who launched Gaurang's Kitchen in Hyderabad in 2022, is now venturing into decor and interior design with Gaurang Home.

Swaroop was conceived after a friend's suggestion to reinterpret Shrinathji – traditionally drawn by Nathdwara do Rajastão artists – in different textual and letterform forms. Now 12 of the 24 pieces have been sold.

Don't be fooled by her smile. Lakshmamma will supervise the mobiles alongside her husband Anaji Rao at Gaurang Shah Homes in Srikakulam district.

Shah sees Swarup as a big change for his Ravi Varma venture, which is centered around khadi jamdani and natural colours. “Swaroop has allowed me to explore Shrinathji through 24 different techniques of Indian textiles and crafts,” he says, with plans to further develop his textile arts series with Ganeshji in the coming year.

To understand the essence of Shah's work—he prefers the term “artist” to “designer”—one need only visit his Jamdani units in Srikakulam, India's oldest technology district Gandhiji, in the state of Andhra Pradesh, in his design study in Hyderabad. The 2019 National Film Award winner for Figurino for Mahanati is often seen dressed in a dark green or dark green linen shirt, Marks & Spencer or Brooks Brothers socks, and crocodile and ostrich fur boots. It involves a relationship of change in the same way as handmade threads, making use of it to explore contemporary themes in keeping with heritage.

This hand-woven Jamdani painting (41 x 50 inches) was created in Srikakulam over 90 days using fresh khadi. Made with intricate yet subtle patterns, the Jamdani technique uses additional weaving, adding fabrics in place of the base fabric to create the motifs.

“In 2003, traveling on the roads to Srikakulam was difficult,” he says, switching effortlessly between Telugu, script and English (with a smattering of Hindi) for the media. “Some families practiced weaving khadi jamdani sarees with simple shoes (small ornaments supported by dyed hair), but their labor was not enough to achieve success.”

What started as a small initiative with artisan Anaji Rao has expanded to 120, forming over 300 women artists, many of whom are vegetable vendors. These handicrafts, now masters of Jamdani Paithanis, are contributing to the reconstruction of two of Ravi Varma's sarees. To modernize the designs and turn them into luxury products, Shah introduced experiments in traditional techniques, ensuring consistent working and sustainable production of the machines, which now earn between Rs 14,000 and Rs 20,000 per month. “This approach also ensures the continuity of my business,” admits Shah.

What do you aspire to create that will last forever?

Gorang Kha: Texts are all about self-education; This is not a design school. Hello, fire. While designers release a collection every six months, they create a new collection every day!

When I started working with computers in 1999-2000, the guide to creativity was written. It shows that innovation was possible by using traditional techniques to create contemporary products – a Fusaw, by Asim Dezer. Today, we collaborate with more than 7,000 artists across 16 to 17 states in India.

Each region of India offers exclusive textiles and handicrafts, each with different designs, hearts and textures. In contrast, countries such as Cambodia, Thailand and Uzbekistan mainly focus on ikat. While they offer only a limited selection of embroidery patterns in Europe, in America they have practically none. The production of machines depends on China. In Japan, we make indigo and shibori hair, and we get jamdanis and khadi from India. However, many design students prefer to imitate the West, preferring dresses with net embroidery rather than handmade dresses.

The industry relies on cheap, low-quality production. Many of Empora's top designers talk about sustainability, and few are truly committed to preserving the art of hand-tearing, or one that requires patience and precision.

Often times, people with low-quality creativity are more disturbed, while our efforts fail. In the final analysis, I want to leave a legacy that celebrates our diverse textile heritage – the premier wonder of the world.